The Space Quest II Master Disk Blunder

There is nothing unusual about the outside of these disks, but there is something unique about the data that is stored on them, something that Sierra On-Line would have been totally unaware of and certainly wouldn’t have wanted them to include.

If you happen to have one of these 720KB floppy disks lurking somewhere in your Sierra adventure game collection, then chances are you are not alone. Versions 2.0D and 2.0F of Space Quest II were not exactly uncommon.

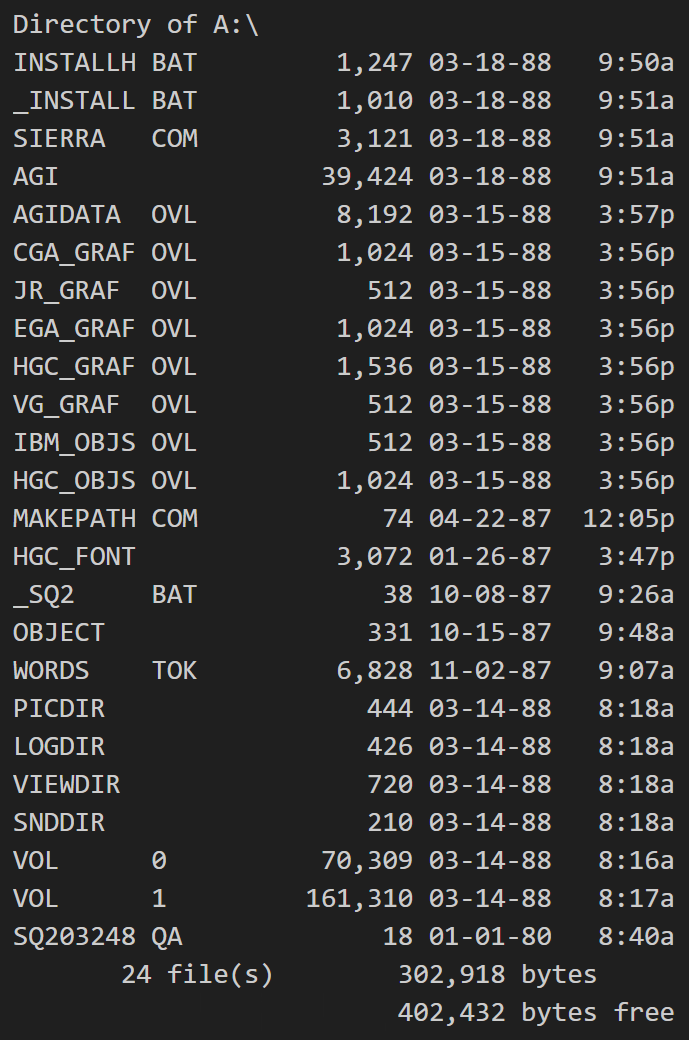

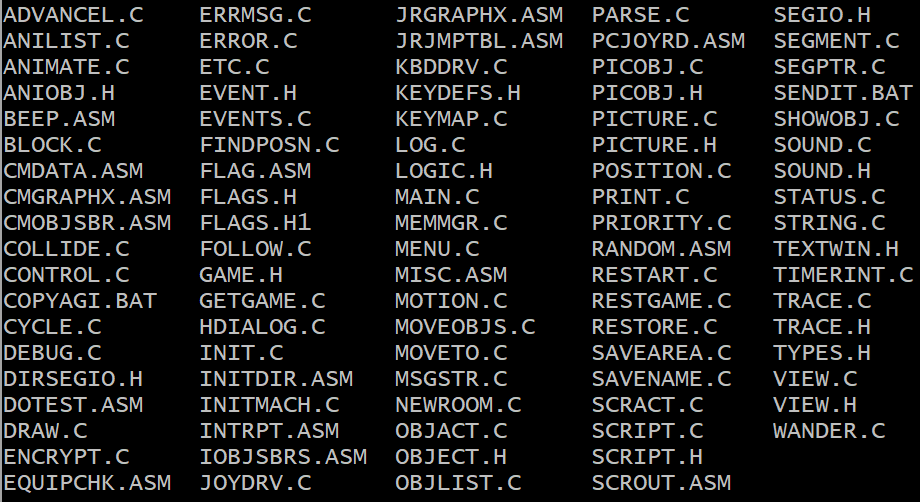

A simple directory listing

Listing the files on the disk doesn’t reveal anything unusual:

The listing shown is from version 2.0D. There are no mysterious additional files, in fact it looks like any other Sierra game disk. Nothing is out of place.

The timestamps show that the game’s main data files, i.e. PICDIR, LOGDIR, VIEWDIR, SNDDIR, VOL.0 and VOL.1, were built on the 14th March 1988. The .OVL files are dated the 15th March 1988, and the AGI interpreter code itself is dated the 18th March 1988. These file timestamps capture a week of activity during which someone in the Sierra office was focused on preparing the 2.0D version of Space Quest II.

One thing that is a little curious about the directory listing above is that the “free” space on the disk is greater than the used space. 302,918 bytes are used and 402,432 bytes are supposedly free.

Using a hex editor

To take a closer look at what is on the disk, and to peek into that supposedly unused part, we need a tool called a hex editor. Back in the 1980s, a commonly used tool for this came with Norton Utilities. These days a great modern equivalent is the excellent HxD Hex Editor written by Maël Hörz.

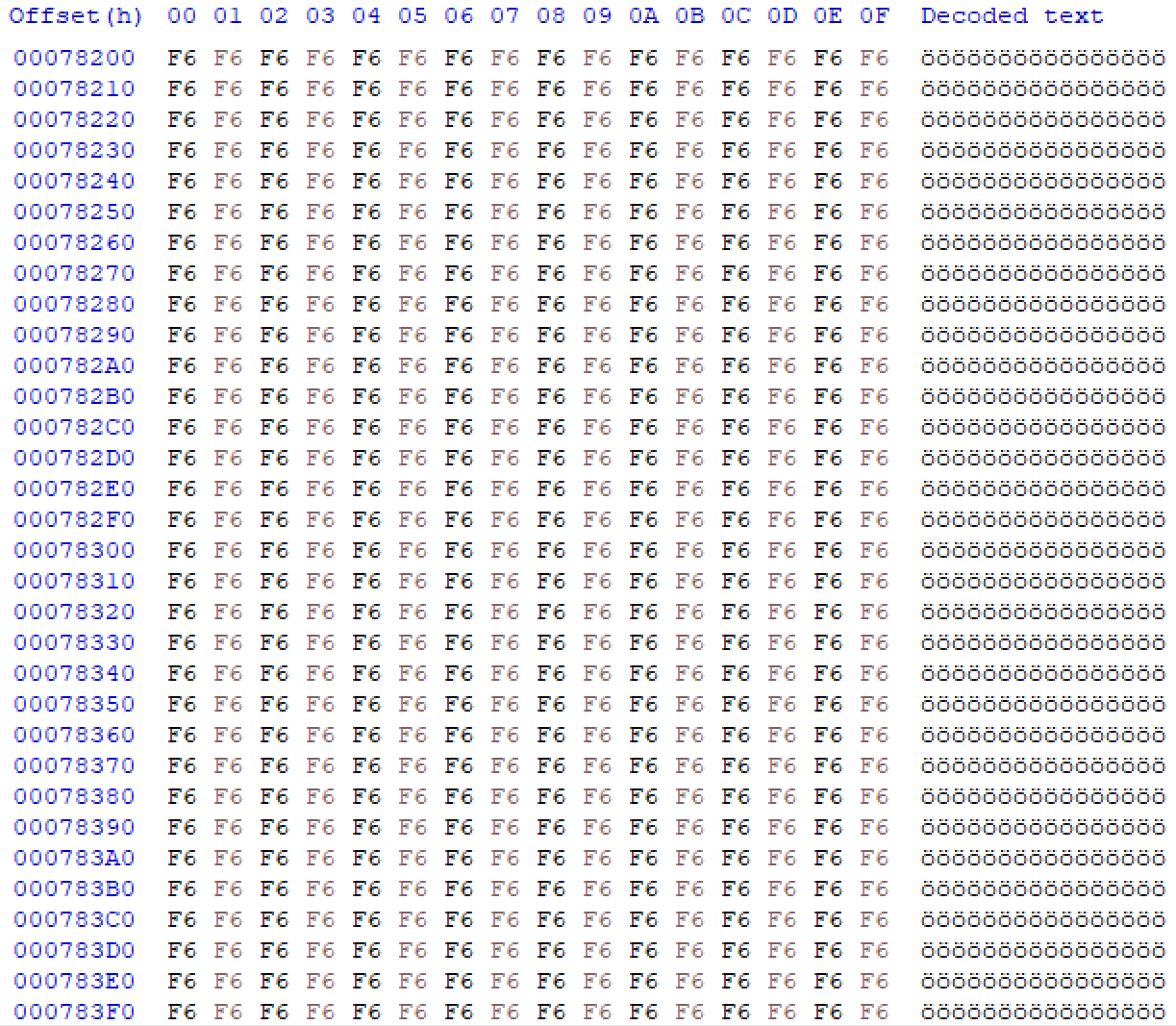

For a freshly formatted DOS floppy disk, we’d expect all of the unused sectors to be filled with the 0xF6 byte value (i.e. DOS’s default format ‘filler’ byte), which is indeed the case for Disk 2 of Space Quest II version 2.0D, as shown below:

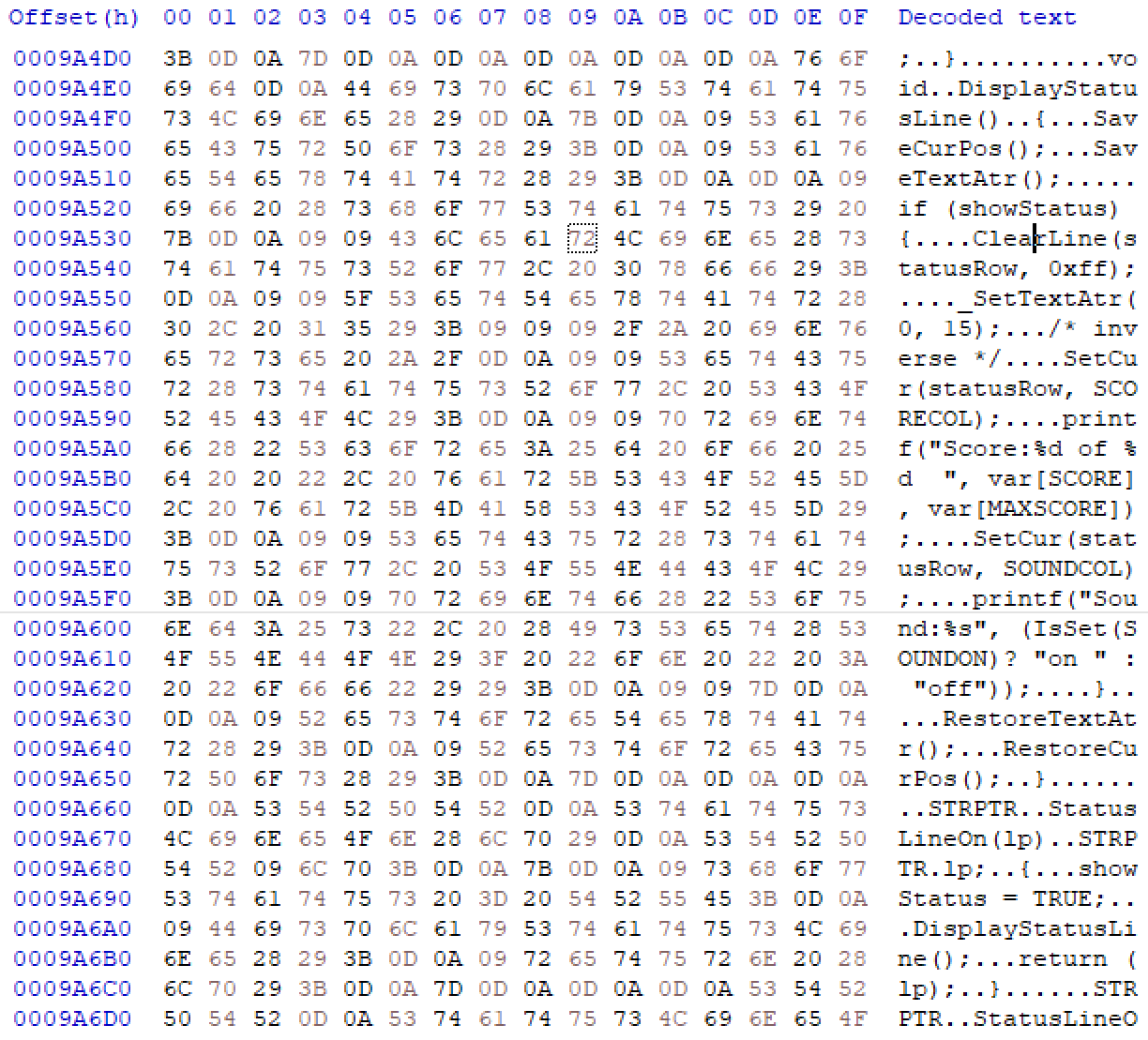

There isn’t, however, a single unused sector on Disk 1 that is filled with the 0xF6 byte, in fact the longest string of consecutive 0xF6 bytes on Disk 1 is only two. Given that over half the disk is “free” space, then clearly the disk had not been formatted prior to being prepared as a SQ2 master disk. The following shows an example of a section of the SQ2 Disk 1 disk that is marked as unused:

Rather than being filled with the 0xF6 byte, it is instead filled with something that looks like C source code. This strongly suggests that the master disk was used for some other purpose prior to being the SQ2 Disk 1 master disk. The files were then deleted, but the disk was not properly formatted afterwards. Due to the way the DOS FAT file system works, deleting a file does not actually remove the data. Instead it simply marks the sectors as no longer being in use, so that in the future they could be used for a new file. If those sectors are never used again for a new file, then they will keep what they previously had stored on them, and so it was important that people fully formatted a floppy disk after storing sensitive files on them.

AGI interpreter source code

It is difficult to see exactly what the above data looks like when viewed in a hex editor, but it clearly looks like text, so let’s copy and paste the ASCII text on the right hand side into a text editor to see what we have:

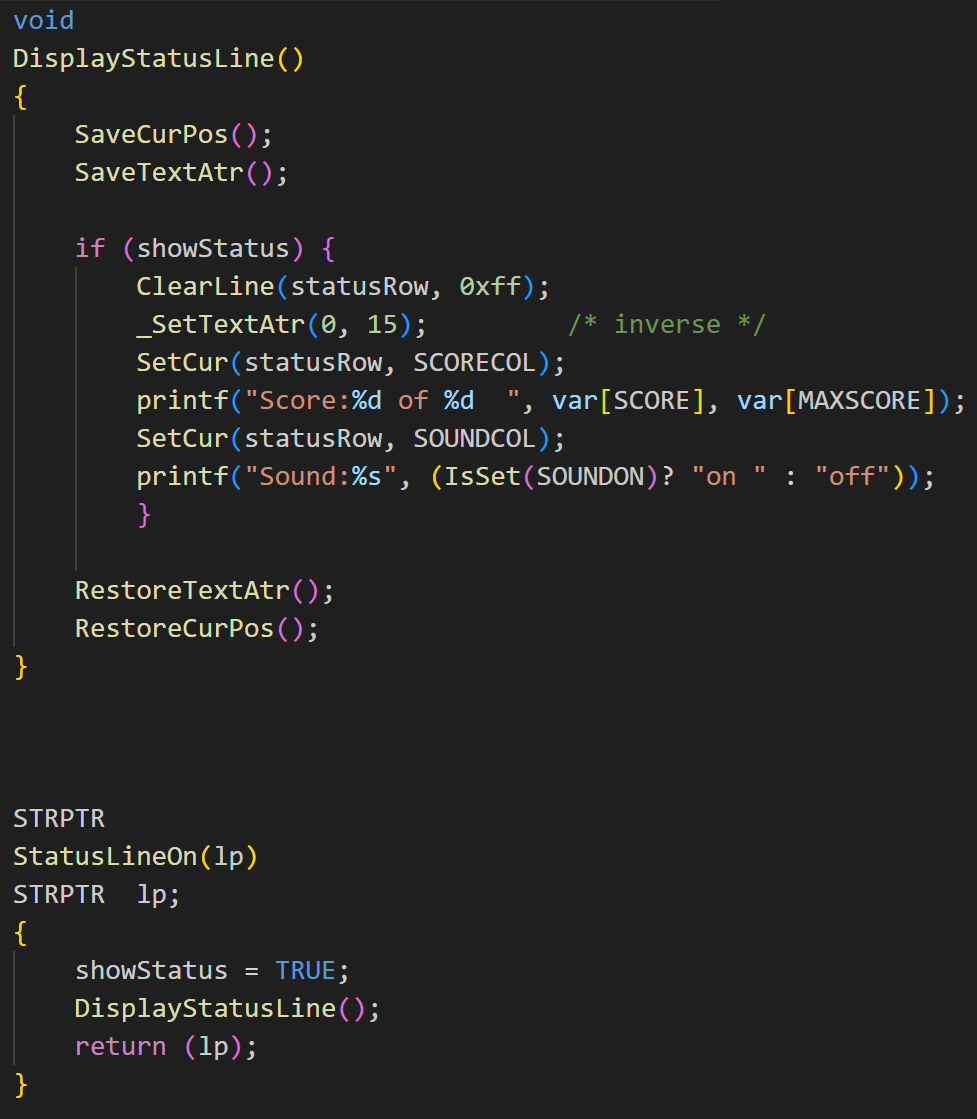

As we can see, it certainly does look like C source code. There are two functions defined, one called DisplayStatusLine and another called StatusLineOn. In the case of DisplayStatusLine, it appears to be displaying a line of text that includes the current score and whether the sound is on or off. Does this look familiar? You bet it does. Take a look at the top of the Space Quest II screen shot below:

That particular piece of C source code is responsible for displaying the white status bar at the top of the game screen, with the black text that shows the user what their current score is. This source code is a part of the AGI interpreter itself!

This is just one small example. Scrolling through more of the unused sectors in the hex editor reveals that there is a large amount of such source code. Not only that but the code is stored over consecutive sectors, i.e. it is not fragmented as you might expect, so it is relatively easy to extract this data from the disk and then split it up into separate C source files. The split points are easy to determine, since each file has a comment at the top saying what the name of the source file is. Splitting into the separate files gives us 93 files in total, made up of 75 C source files, 16 assembly language source files, and 2 DOS BAT files:

In total, there are over 15000 lines of code and most of these files are complete.

It turns out that this Space Quest 2 game disk contains about 70% of the source code of Sierra On-Line’s AGI interpreter, complete with comments and change history. We will look at how that 70% figure was calculated later in the article.

When we say “the AGI interpreter”, what we are referring to is the file named “AGI” in the directory listing that was shown earlier, along with the the .OVL files. The “AGI” file is the executable that performs the actual interpretation of the game data contained in the LOGDIR, PICDIR, VIEWDIR, SNDDIR, OBJECT, WORDS.TOK and VOL files.

Source file change history

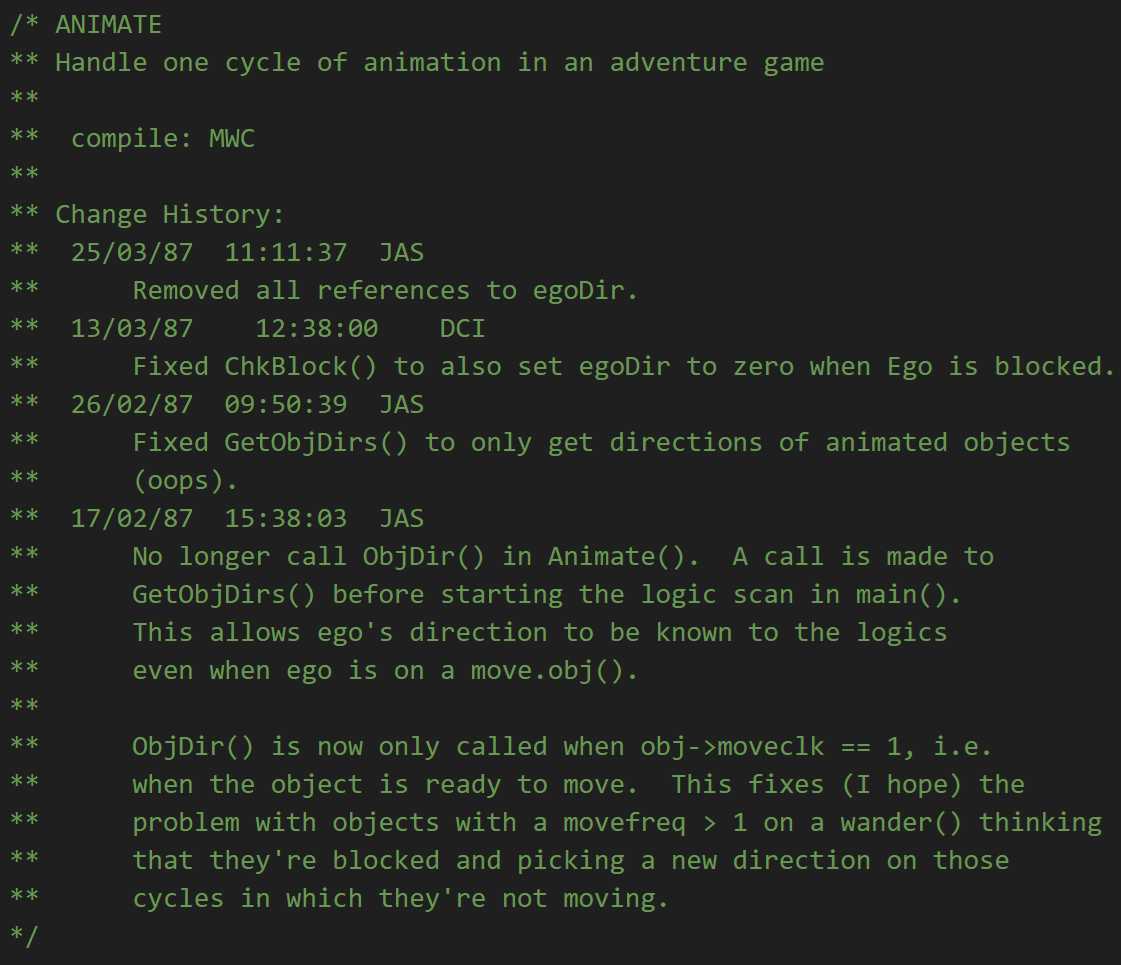

Some of the source files contain a change history within the header comment at the top. The following is an example from the ANIMATE.C source file:

The header comment starts by stating the name of the source file. It then gives a short description of what it does, in this case to “Handle one cycle of animation in an adventure game”. Next we have a line that says “compile: MWC”. This appears to state the name of the C compiler that was used to compile the C source. MWC was a C compiler from the Mark Williams company that was very popular in those days. After that, the header has a “Change History” section and this makes for very interesting reading. It mentions the date, time, initials of the person making the change, and a description of the change.

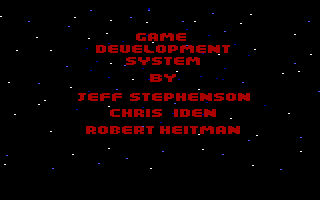

The programmers have identied themselves using their initials, including their middle name initial. JAS is none other than Jeff Stephenson, the main programmer who was working on the AGI interpreter code, and DCI is Chris Iden. If you look at the game credits for the AGI games from 1985-89, you will see that Jeff and Chris were always credited with working on the game development system.

Robert Heitman is also listed, but his focus was mainly on the graphics tools (i.e. the Picture Editor (PE) and View Editor (VE)), whereas Jeff and Chris worked primarily on the interpreter code. So it isn’t surprising to see their initials in the change history for the C source code of the AGI interpreter.

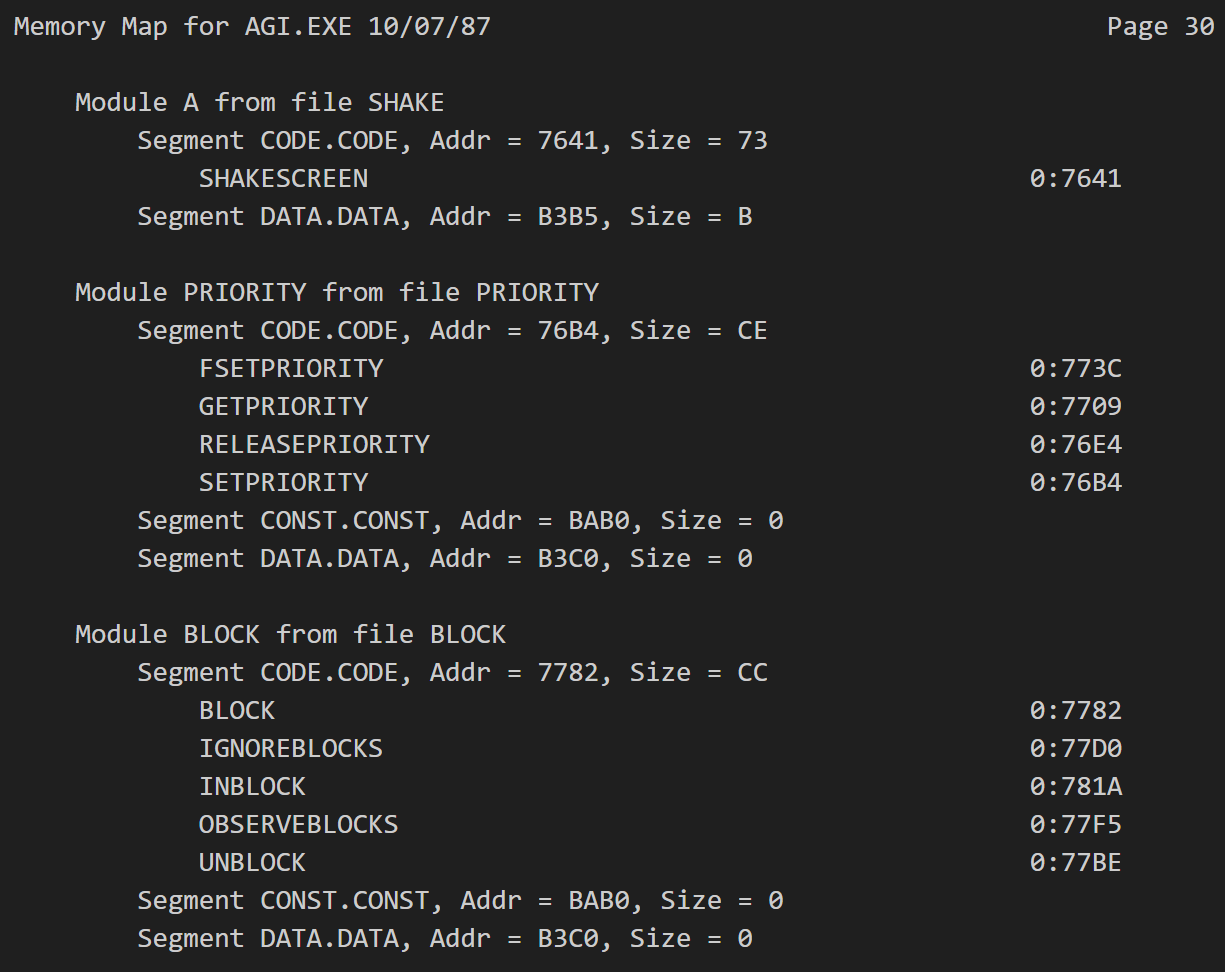

AGI.EXE memory map

In addition to the 93 AGI interpreter source code files, the SQ2 2.0D 720KB Disk 1 disk also contains over 2000 lines of a Memory Map of the AGI.EXE executable. For production releases of AGI games, the interpreter executable is called simply AGI, and is not directly executable, but during the development of the games, Sierra On-Line used a version of the interpreter that had the .EXE extension and could be run directly. Someone at Sierra generated a memory map of the AGI.EXE executable, i.e. the AGI interpreter, on the 7th October 1987. A small section of it is shown below:

This gives a potential date to the collection of source code files. It ties in with the most recent change history comment in the code, which is from September 1987.

The memory map also gives us a fairly complete list of the modules and source files that make up the AGI interpreter. Each module specifies the file that it is defined in. If we count the number of distinct source files mentioned, it comes to 98. The number of those source files that are present in full on the SQ2 disk is 71. This is where we get the figure of roughly 70% for the amount of AGI interpreter source code that is on the SQ2 disk. For some of the modules, only the C header file is included, and so those modules are not included in this calculation.

Sierra’s intellectual property

In 1984, Sierra On-Line was lucky to survive as a business. Some time around the release of King’s Quest, in May/June of that year, Ken Williams had to lay off around 100 of his employees, reducing the head count from approximately 130 down to about 30. Although it was a struggle, part of what turned their fortunes around was the success of the AGI adventure game system and the games that were built using it. By the end of 1984, King’s Quest had entered the top 20 on the software sales charts for computer games. It would stay there for the next half year, right up until the release of King’s Quest II, and it wasn’t long until King’s Quest II was also in the charts. This was helped a lot by the deal that Sierra made with Tandy Radio Shack to sell Tandy versions of the games in the Radio Shack stores.

The AGI games continued to be best sellers from 1985 to 1988. Over those years, the AGI interpreter was Sierra On-Line’s primary means of making money and therefore a core part of their intellectual property. They not only invented the 3D animated graphic adventure game genre but also had a head start on their competitors that lasted several years. It is safe to say that the source code for the AGI interpreter is something that Sierra would have preferred didn’t fall into the hands of their competitors.

For 70% of the source code to end up being copied en masse and sent out to tens, if not hundreds of thousands of their customers, was a big blunder.

How did this happen?

When a new release version of a game was prepared by Sierra, it involved creating a “production copy” master disk to be used by the FormMaster disk duplication machine. This machine did not simply copy files from the the master disk to each copy but instead copied every byte of every sector of the disk, regardless of whether the sectors were currently being used or not. What this meant in the case of the version 2.0D and 2.0F SQ2 Disk 1 disks is that it also copied the supposedly unused 402,432 bytes, despite there being no reason to. This is why the preparation of a master disk involved ensuring that it started out fully formatted before the game was copied on to it, and for the most part, Sierra On-Line got this step right. Most original Sierra game disks were formatted before use. It would seem that someone forgot to do this for the Space Quest II version 2.0D Disk 1 disk, and the same disk was then also used for version 2.0F of SQ2.

This meant that potentially hundreds of thousands of SQ2 disks sent to customers and retail stores had a copy of 70% of the AGI interpreter source code hidden on them.

Dodged a bullet

It was almost certainly an unintentional mistake. Surprisingly, no one appeared to have noticed that this happened, not Sierra, not their competitors or their customers, and it was only discovered decades later, the first known discovery of it by online user NewRisingSun in October 2016.

It is also fortuitous that this happened at the end of the AGI era. In March 1988, Sierra had already developed their SCI adventure game system and were about to release the first game using it, which would be King’s Quest IV. So accidentally leaking the AGI interpreter source code into the public, should someone have noticed it, may not have been the issue it could have been only a year or two before that.

It makes for an interesting digital archeaology story though, and it allows us, 36 years later, to see how our heros at Sierra On-Line wrote their AGI interpreter.

For those who are interested, I have uploaded the extracted AGI interpreter source code into a github repo: https://github.com/lanceewing/agi

Check out AGILE, the web based AGI interpreter, whose implementation was guided in part by the original AGI source code.